Extracurricular physical activities practiced by children: relationship with parents’ nutritional status and level of activity

Research

- 22Downloads

Abstract

Purpose

Sedentarism is a global epidemic that engages 60 to 70% of the global population. A progressive physical activities decline occurs from childhood to adolescence. This study aims to compare extracurricular physical activity among students with and without overweight and to relate it to the level of physical activity of their parents.

Methods

This cross-sectional study evaluated 375 children aged 6–11 years from two public schools that have extracurricular and optional activities. Data collected: weight and height for the calculation of body mass index and height/age z-scores; waist circumference to calculate waist to height ratio; extracurricular physical activity of children and parents/caregivers (short version of the IPAQ—International Physical Activity Questionnaire).

Results

Mean age was 8.7 ± 1.4 years in the studied population; overweight and obesity was observed in 98 (26.8%) and 79 (21.6%) children, respectively. Extracurricular physical activity was observed in 86 (22.9%) children. Physical activity of parents was not associated with children’s practice or their nutritional status. No difference was found in relation to physical activity and nutritional status. However, boys were less engaged in physical activities compared with girls (32–37.2% vs 54–62.8%, p = 0.003).

Conclusion

Considering the importance of promoting children’s physical activity and based on the results evidenced in this study highlighting the low demand for physical activity provided by schools, stimulating measures by educators and family members are clearly required.

Keywords

Child Physical activity Sedentary behavior Obesity

Abbreviations

- IPAQ

-

International Physical Activity Questionnaire

- PA

-

physical activity

- WHO

-

World Health Organization

- POF

-

Household Budget Survey

- FNDE

-

National Education Development Fund

- PENSE

-

National School Health Survey

- CESAs

-

Santo Andre Educational Centers

- ZBMI

-

score Z body mass index

- ZHA

-

score Z height for age

Introduction

Sedentarism is a global epidemic that engages 60 to 70% of the global population [1]. In Brazil, the 2014 Vigitel report showed that leisure physical activity (PA) frequency (at least 150 min moderate intensity per week) ranged from 30.4% (São Paulo) to 47.1% (Florianópolis) [2]. It is worth noting that, in Brazil, only 29% of adolescents achieve the World Health Organization (WHO) recommendation (≥ 60 daily minutes of moderate/vigorous intensity PA), a setting similar to other Latin American countries (10–20%) and in the world (20%).

A progressive PA decline occurs from childhood to adolescence. The multicenter International Children’s Accelerometry Database, which included data from Europe, North America, Australia and Brazil, showed a 4.2% yearly decrease in PA [3].

Physical inactivity is one of the most important risk factors for the development of chronic diseases, such as obesity, diabetes, and hypertension, and fight against such diseases is included in the public health policy agenda in several countries [4].

In Brazil, according to the 2008–2009 Household Budgets Survey (POF), an increased high prevalence of overweight and obesity was found among children aged 5–9 years, of 33.5% and 14.3%, respectively. Rates observed for adolescents were 20.5% and 4.9%, respectively [5].

It is known that children that are more active have a lower body mass index and a lower percentage of fat. In addition, obese children, compared with non-obese children, are less active and prefer low intensity activities as opposed to moderate and/or vigorous intensity activities [6].

The WHO recommends that children and adolescents aged 5–17 years should accumulate at least 60 min of moderate/vigorous intensity PA every day. Most of the activities should be aerobic. Vigorous intensity, including muscle and bone strengthening exercises should be incorporated at least 3 times per week [1].

Several factors contribute to the sedentary lifestyle in the pediatric age group: technology, insecurity and reduced space available for practicing PA in urban centers. Systematic review of Latin American literature in the field of physical activity interventions concluded that the promotion of physical activity in the school environment is highly recommended and effective [7].

In the USA, extracurricular PA programs in schools serve more than 10 million children annually and have shown to be effective in reducing the time spent in sedentary activities and in proposing at least 30 min of activities of moderate/vigorous intensity [8]. In Brazil, projects that make PA available at weekends and/or school counter-shifts are already a reality in several schools and are supported by current legislation and the proposal of the National Education Development Fund (FNDE) [9]. The National School Health Survey (PeNSE) included a representative sample of seniors (9th graders) from elementary school (2842 schools and 110,873 students) in 2012, and showed that extracurricular PA in schools was positively associated with increased level of leisure and total PA [10].

Given prior knowledge that children PA is effective in the prevention of obesity and other chronic diseases and contributes to improved strength, balance, flexibility, aerobic resistance, and speed, favoring healthy growth and even school performance, and the lack of studies evaluating the demand for school extracurricular physical activities justifies this study that aims to compare extracurricular physical activity among students with and without overweight and to relate it to the level of physical activity of their parents.

Methods

Study design

In the period January–December 2014, this cross-sectional study evaluated 375 primary school children aged 6–11 years from two public schools located in the outskirts of the Municipality of Santo André.

Schools were selected by convenience, because they were in nearby districts, with similar socioeconomic characteristics, extra-curricular structure and physical activities, and a high percentage of children in the chosen age group.

The selected schools are linked to the Santo André Educational Centers (CESAs) of Vila Sá (n = 181 students) and Vila Palmares (n = 194 students). CESAs are recreational spaces, of which schools are an integral part. They are equipped with sports courts, soccer fields, skating rinks, playgrounds, recreational squares, hiking trails, and fitness areas, as well as libraries and multipurpose rooms [11].

CESAs’ activities are extracurricular, optional, developed by physical educators and mainly attend to elementary school students. The studied CESAs’ activities are capoeira, dance, artistic fitness, taekwondo, and athletics [11]. Lessons last 60 min twice a week, except athletics, which occurs once a week.

Children should be regularly enrolled in CESAs-linked schools in the 2014 school year and give their consent to participate in the study in order to be included in the study. Children with chronic diseases, except obesity, such as genetic and neurological diseases, myopathy, orthopedic diseases, and diseases involving restricted physical activity were excluded.

To calculate the sample, we considered that the correlation between vigorous physical activity and body mass index in a sample of Brazilian schoolchildren was r = − 0.142. Adopting α = 5% and β = 80%, we would require 378 students to evaluate this possible association in our study [12].

The Research Ethics Committee of the Faculdade de Medicina do ABC approved and authorized the study under No. 066275/2014. All children and parents involved signed the informed consent form.

Anthropometric evaluation

The weight and height data [13] used to calculate z-scores of body mass index (ZBMI) and height/age (ZHA) were collected at the school through the WHO Anthro Plus ® program. The cutoff points adopted followed the WHO recommendation, 2007 [14]: ZBMI > + 3—severe obesity; + 3 ≥ ZBMI > + 2—obesity; + 2 ≥ ZBMI > + 1—overweight; + 1 ≥ ZBMI > − 2—eutrophy; − 2 ≥ ZBMI > − 3—thinness; and ≤ − 3—accentuated thinness. For the ZHA, values < − 2 were classified as low height.

Abdominal circumference was measured at midpoint between the last fixed rib and upper iliac crest, with an inextensible tape measure. We calculated the waist to height ratio (cm/cm), and values above 0.5 were deemed inadequate (central obesity) [15].

Children’s physical activity

To obtain data on extracurricular physical activity, we consulted all the lists of enrollment and attendance between the months of April and December of 2014. To participate in the classes, students must enroll in the chosen activity (ies), and the teacher checks the attendance during the school year. Students can drop out or change their chosen activity throughout the year. If they miss more than three times without justification, they are removed from the activity.

Parents/caregivers physical activity

The short version of the IPAQ (International Physical Activity Questionnaire) questionnaire [16, 17] was applied for self-completion to evaluate the physical activity and sedentary behavior of parents/caregivers. This evaluation ranks individuals into five categories: very active, active, irregularly active A, irregularly active B, and sedentary.

Statistical analysis

Data were entered and consolidated in the Excel spreadsheet (Office MS ®) and analyzed in statistical package SPSS 24.0 (IBM ®). Categorical variables were shown as absolute and percentage numbers, compared using the chi-square test or the Fisher exact test. Continuous variables were tested for normality. Those following a normal distribution were shown as mean ± standard deviation and compared by Student t test. Those that did not follow normal distribution were shown as median (interquartile range) and compared by Mann-Whitney Utest. The significance level adopted was 5%.

Results

Characterization of the studied population

|

Variable |

Schools (n = 375) |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Gender |

Male |

193 (51.5%) |

|

Female |

182 (48.5%) |

|

|

Age |

Years |

8.7 ± 1.4 |

|

Body mass index score Z |

Malnutrition |

2 (0.5%) |

|

Eutrophy |

186 (50.9%) |

|

|

Overweight |

98 (26.8%) |

|

|

Obesity |

59 (16.2%) |

|

|

Severe obesity |

20 (5.4%) |

|

|

Height for age index score Z |

Short stature |

6 (1.6%) |

|

Normal stature |

359 (98.3%) |

|

|

Waist/height |

Aumentada |

123 (33.6%) |

|

Adequada |

242 (66.3%) |

|

|

Physical activity practice |

Yes |

86 (22.9%) |

|

No |

289 (77.1%) |

|

|

Physical activity type |

Athletics |

22 (25.6%) |

|

Capoeira |

16 (18.6%) |

|

|

Circus |

8 (9.3%) |

|

|

Dance |

16 (18.6%) |

|

|

Fitness |

21 (24.4%) |

|

|

Taekwondo |

3 (3.5%) |

|

|

Physical activity by parents |

Very active |

92 (27.5%) |

|

Active |

122 (36.5%) |

|

|

Irregularly active A |

34 (10.2%) |

|

|

Irregularly active B |

59 (17.7%) |

|

|

Sedentary |

27 (8.1%) |

|

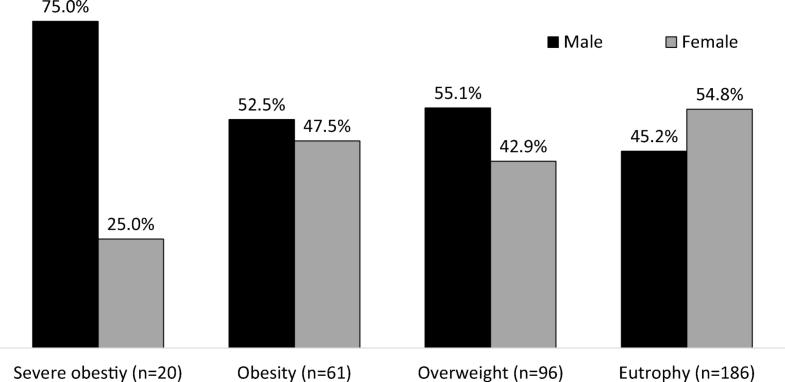

Children’s nutritional status in relation to gender. Asterisk symbol indicates significance level of the chi-square test (p = 0.041)

There was no difference in gender and age between the two schools, and the options of activities that children could participate in were similar in both schools. Extracurricular physical activity was observed in 86 (22.9%) children. Among those who were engaged in some modality, the most popular were fitness 21 (24.4%), athletics 22 (25.6%), and dance 16 (18.6%) (Table 1).

Relationship between children’s nutritional status and parents’ physical activity

|

Variable |

Active and very active (n = 214) |

Irregularly active A and B (n = 93) |

Sedentary (n = 27) |

pvalue |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Nutritional status |

Obesity |

43 (20.1%) |

16 (17.2%) |

5 (18.5%) |

0.513 |

|

Overweight |

64 (29.9%) |

21 (22.6%) |

5 (18.5%) |

||

|

Eutrophy |

104 (48.6%) |

53 (57.0%) |

15 (55.5%) |

||

|

Children’s physical activity |

Yes |

53 (24.8%) |

21 (22.6%) |

5 (18.5%) |

0.741 |

|

No |

161 (75.2%) |

72 (77.4%) |

22 (81.5%) |

||

Relationship between nutritional status and physical activity

|

Variable |

Practices (n = 86) |

No practices (n = 279) |

p value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Nutritional status |

Severe obesity |

4 (4.6%) |

16 (5.7%) |

0.755 |

|

Obesity |

13 (15.1%) |

48 (17.2%) |

||

|

Overweight |

26 (30.2%) |

70 (25.1%) |

||

|

Eutrophy |

41 (47.7%) |

145 (52.0%) |

||

Comparing physical activity between boys and girls, with adjustment for nutritional status

|

Variable |

Practices (n = 86) |

No practices (n = 279) |

Total |

p value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Obesity |

Male |

6 (35.3%) |

41 (64.0%) |

47 |

0.032 |

|

Female |

11 (64.7) |

23 (35.9%) |

34 |

||

|

Total |

17 |

64 |

81 |

||

|

Overweight |

Male |

13 (50%) |

41 (58.6%) |

54 |

0.300 |

|

Female |

13 (50%) |

29 (41.4%) |

42 |

||

|

Total |

26 |

70 |

96 |

||

|

Eutrophy |

Male |

13 (31.7%) |

71 (48.9%) |

84 |

0.036 |

|

Female |

28 (68.3%) |

74 (51.0%) |

102 |

||

|

Total |

41 |

145 |

186 |

||

Discussion

In the present study, we observed that the children’s demand for PA in the extracurricular period was low and did not differ in relation to the nutritional status. A recent study with children from Florianópolis showed that the time spent with sedentary activities in the school period exceeded two-thirds of the total daily schedule [18]. Another study showed that Brazilian children spend 65% of the time in physical education classes, sitting or standing still, that is, without moving or developing vigorous activities [19].

Considering the results of the studies cited, we would infer that, along with other factors, educators provide little incentive to children for PA in the curricular period, which can reflect in the search for PA in schools’ counter-shifts. Other hypotheses may explain such a finding, such as the lack of parents’ appreciation of the importance of physical activity as child health promotion, children mobility constraints to go to school after regular hours, and lack of interest in the activities offered. An Australian study involving four schools listened to students in order to investigate how the school environment could be explored better as an incentive to engage in activities. Students suggested that improved physical spaces, such as installation of climbing walls, outdoor excursions, and the inclusion of music during activities could stimulate the practice [20].

There was no association between the demand for PA and the nutritional status of children in our study. A recent publication performed in 12 countries, including Brazil (n = 6,025 children aged 9–11 years), contrary to what we observed, showed an association between obesity and behaviors as a short time dedicated to activities of moderate/vigorous intensity, shorter sleep duration, and more time spent watching television [21].

In the study, we also verified that less than 10% of the parents were classified as sedentary and 36% as insufficiently active (sedentary+irregularly active). Using IPAQ’s short version, which included walking, interviewing 2001 people aged 14–77 years (953 males and 1048 females) from the State of São Paulo, Matsudo et al. 2002 [22] showed higher levels of sedentary lifestyle (21.2%) compared with what we observed. A study considering a Brazilian sample reported that individuals with higher level of schooling were physically more active in leisure compared with those with less schooling, who were more active at work [23]. Thus, one must consider the limitations regarding the tool used, namely IPAQ short version, which is unable to distinguish physical activity realms (leisure, occupational, housework, and travel).

We still did not find an association between the level of activity of parents and children’s search for physical activity. A study carried out with a sample of 1042 preschool children from Recife, Brazil, corroborating with our findings, found no association between the level of physical activity of parents and children [24]. A possible explanation for this lack of association may be the tool used to evaluate parents, considering that most of the studies in which this association was observed employed direct methods such as accelerometry to measure PA [25, 26].

In our study, we noted that boys practiced less physical activity compared with girls, even after adjustment for nutritional status. Studies in the literature show results discordant to ours. CESAs’ most sought-after activities, among which are fitness, athletics, and dance, may have favored this finding. A study conducted in Rio Grande do Sul evaluated the participation of adolescents in physical activities, according to gender and sports modality. Among male participants, the top-three modalities were soccer (82.5%), volleyball (18.2%), and bodybuilding (10.8%). Among female participants, volleyball (46.3%), dance (25.4%), and fitness (18.5%) prevailed. Around 8.5% of men and only 1.9% of women were engaged in martial sports, while 25.4% of women and only 3.8% of men were involved with dancing [27].

This is the first study evaluating the children’s demand for extracurricular physical activities in Educational Centers located in the outskirts of the Municipality of Santo André. Some limitations deserve consideration, such as the cross-sectional study design and the use of a questionnaire to assess the level of parental physical activity rather than the use of direct measures such as accelerometry.

Physical inactivity is a global concern, and alarming data in the pediatric age group require special attention and urgent proposals. Considering the importance of stimulating children’s physical activity and based on the results shown here highlighting the low demand for physical activity offered in schools, the need for stimulating measures by educators and relatives is all the more pressing. Future projects involving broad sensitization work by teams involved should be considered.

Notes

Acknowledgments

Núcleo de Estudos, Pesquisas e Assessoria à Saúde da Faculdade de Medicina do ABC (NEPAS) da Faculdade de Medicina do ABC.

Compliance with ethical standards

The Research Ethics Committee of the Faculdade de Medicina do ABC approved and authorized the study under No. 066275/2014. All children and parents involved signed the informed consent form.

References

-

1.World Health Organization. Global strategy on diet, physical activity and health. WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data. Geneva, 2004. http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/strategy/eb11344/strategy_english_web.pdf. Access on 24/07/2016.

-

2.Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Departamento de Vigilância de Doenças e Agravos não Transmissíveis e Promoção da Saúde. Vigitel Brasil 2014: vigilância de fatores de risco e proteção para doenças crônicas por inquérito telefônico / Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde, Departamento de Vigilância de Doenças e Agravos não Transmissíveis e Promoção da Saúde. – Brasília: Ministério da Saúde, 2015. 152 p. http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/vigitel_brasil_2014.pdf. Access on 24/07/2016.

-

3.Cooper AR, Goodman A, Page AS, Sherar LB, Esliger DW, van Sluijs EM, et al. Objectively measured physical activity and sedentary time in youth: the international children’s accelerometry database (ICAD). Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2015;12:113. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-015-0274-5.CrossRefPubMedPubMedCentralGoogle Scholar

-

4.Pratt M, Perez LG, Goenka S, Brownson RC, Bauman A, Sarmiento OL, et al. Can population levels of physical activity be increased? Global evidence and experience. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2015;57(4):356–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2014.09.002.CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

-

5.Ministério do Planejamento, Orçamento e Gestão Instituto Brasileiro de Geografi an e Estatística – IBGE Diretoria de Pesquisas Coordenação de Trabalho e Rendimento. Pesquisa de Orçamentos Familiares 2008-2009. Antropometria e Estado Nutricional de Crianças, Adolescentes e Adultos no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro, 2010.Google Scholar

-

6.Trost SG. Objective measurement of physical activity in youth: current issues, future directions. Exec Sport Sci Rev. 2001;29(1):32–6.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

7.Boehner CM, Soares J, Parra Perez D, Ribeiro IC, Joshua CE, Pratt M, et al. Physical activity interventions in Latin America: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(3):224–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2007.11.016.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

8.Beets MW, Weaver RG, Turner-McGrievy G, Huberty J, Ward DS, Pate RR, et al. Physical activity outcomes in afterschool programs: a group randomized controlled trial. Prev Med. 2016;90:207–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.07.002.CrossRefPubMedPubMedCentralGoogle Scholar

-

9.Fundo Nacional de Desenvolvimento da Educação (FNDE). http://www.fnde.gov.br/programas/par/par-apresentacao. Access on 26/07/2016.

-

10.Rezende LF, Azeredo CM, Silva KS, Claro RM, França-Junior I, Peres MF, et al. The role of school environment in physical activity among Brazilian adolescents. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0131342. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0131342.CrossRefPubMedPubMedCentralGoogle Scholar

-

11.Giro ER. Centros Educacionais de Santo André: Novas formas de organização da escola pública. Dissertação de Mestrado do programa de pós-graduação da Universidade Metodista de São Paulo, São Bernardo do Campo. São Paulo, 2008.Google Scholar

-

12.Ferrari GL, Oliveira LC, Araujo TL, Matsudo V, Barreira TV, Tudor-Locke C, et al. Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity and sedentary behavior: independent associations with body composition variables in Brazilian children. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2015;27(3):380–9. https://doi.org/10.1123/pes.2014-0150.CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

-

13.World Health Organization Physical Status: The use and interpretation of anthropometry Report of WHO Expert Committee. World Heath Organ. Tech. Rep. Su 1995;854:1–452.Google Scholar

-

14.de Onis M, Ouyang AW, Burgh E, Siam A, Nishida C, Siemen J. Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85(9):660–7.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

15.Browning LM, Hsieh SD, Ashwell M. A systematic review of waist-to-height ratio as a screening tool for the prediction of cardiovascular disease and diabetes: 0·5 could be a suitable global boundary value. Nutr Res Rev. 2010;23(2):247–69.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

16.Hallal PC, Gomez LF, Parra DC, Lobelo F, Mosquera J, Florindo AA, et al. Lessons learned after 10 years of IPAQ use in Brazil and Colombia. J Phys Act Health. 2010;7(Suppl 2):S259–64.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

17.Pardini R, Matsudo SM, Araújo T, Matsudo V, Andrade E, Braggion G, et al. Validation of the International Physical Activity Questionaire (IPAQ-version 6): pilot study in Brazilian young adults. Rev Bras Ciên e Mov. 2001;(3):45–51.Google Scholar

-

18.da Costa BG, da Silva KS, George AM, de Assis MA. Sedentary behavior during school-time: Sociodemographic, weight status, physical education class, and school performance correlates in Brazilian schoolchildren. J Sci Med Sport. 2017;20(1):70-74. Google Scholar

-

19.Hino AAF, Reis RS, Añez CRR. Observação dos níveis de atividade física, contexto das aulas e comportamento do professor em aulas de educação física do ensino médio da rede pública. Rev Bras Ativ Fís Saúde. 2007;12:21–30.Google Scholar

-

20.Hyndman B. A qualitative investigation of Australian youth perceptions to enhance school physical activity: the environmental perceptions investigation of children’s physical activity (EPIC-PA) study. J Phys Act Health. 2016;13(5):543–50. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2015-0165.CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

-

21.Katzmarzyk PT, Barreira TV, Broyles ST, Champagne CM, Chaput JP, Fogelholm M, et al. ISCOLE research group. Relationship between lifestyle behaviors and obesity in children ages 9-11: results from a 12-country study. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2015;23(8):1696–702. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.21152.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

22.Matsudo SM, Matsudo VR, Araújo T, Andrade D, Andrade E, Oliveira LC, et al. Nível de atividade física da população do Estado de São Paulo: análise de acordo com o gênero, idade, nível sócio-econômico, distribuição geográfica e de conhecimento. Rev Bras Ciênc Mov. 2002;10:41–50.Google Scholar

-

23.Nunes AP, Luiz Odo C, Barros MB, Cesar CL, Goldbaum M. Domains of physical activity and education in São Paulo, Brazil: a serial cross-sectional study in 2003 and 2008. Cad Saude Publica. 2015;31(8):1743–55.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

24.Wanderley RS Jr, Hardman CM, Oliveira ES, Brito AL, Barros SS, Barros MV. Fatores parentais associados à atividade física em pré-escolares: a importância da participação dos pais em atividades físicas realizadas pelos filhos. Rev Bras Ativ Fis Saúde. 2013;18(2):205–14.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

-

25.Loprinzi PD, Trost SG. Parental influences on physical activity behavior in preschool children. Prev Med. 2010;50(3):129–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.11.010.CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

-

26.Oliver M, Schofield GM, Schluter PJ. Parent influences on preschoolers’ objectively assessed physical activity. J Sci Med Sport. 2010;13(4):403–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2009.05.008.CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

-

27.Azevedo MR, Araújo CL, Cozzensa da Silva M, Hallal PC. Tracking of physical activity from adolescence to adulthood: a population-based study. Rev Saude Publica. 2007;41(1):69–75.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Copyright information

Open AccessThis article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.